Living a Still Life

I’ve been having a peruse into the past, and found this article by my friend Louise Steinman, who visited me on Crete several times over the 20 years I was there. I hope you’ll enjoy it.

Peace on Earth; Living a Still Life; On the Island of Crete, Sharing an Artist’s Vision

By Louise SteinmanWashington Post

December 20, 1992

Three hours to go until the ferry leaves Piraeus. I ponder a snapshot of an old stone house, painted robin’s-egg blue. It’s the only blue house in Gerani, the village in Crete where my old friend Scotty lives. The color of the house is a clue to its inhabitant’s calling.

Scotty is a painter of landscapes and still lifes. Crete has been her home for the past 15 years. At 26, alone, she decided to settle on the island. She’d fallen in love with the landscape and figured it would be a cheap home base for a painter. She picked a village in the mountains, Spili, and moved there. I don’t know how she ever had the guts.

From my secure vantage point at the time, I followed her life’s choices with awe. She was the first foreigner ever to live in Spili. She had an affair with a villager who still lived with his parents. “I was too young and too in love to care about the scandal,” she says now with a laugh. They’d meet at a designated spot outside the village. She would climb on the back of Manolis’s motorbike (papaki, or “little duck”) and they would zoom off in the balmy night air to summer festivals in nearby villages. One night, after she told him it was over, he broke down her front door. Great stormy stuff. I’m sure the villagers were delighted with the drama.

Seven years ago Scotty bought the house in Gerani. She has a large room under the house (meant for goats) for her painting studio. In letters over the years she has sounded happy. Poor, but happy. She’s been able to support herself as a painter of landscapes and still lifes, selling her work at galleries in Europe.

A truckful of unhappy billy goats are loaded onto the ferry beside mine. The sounds of their raucous discomfort accompanies me as I wander into the crowded lounge. The ferry is full. Everyone smokes, right under the “no smoking” signs. A Gypsy man walks through the lounge, lifting his shirt to show a long scar. He carries a scrapbook documenting his misfortune. A few people give him drachmas.

I am hoping to find in the quiet of fall in Gerani an antidote to my frenetic life in Los Angeles. What better way to understand a still life painter, than to live in the still life?

Early morning, Souda Harbor. I hope I told Scotty the right date. Then, standing at the rail, I see her waving. She’s a sturdy woman with strong handsome features. If you didn’t know otherwise, she could pass for Greek, her skin bronzed from years of painting outdoors. How did it happen that we were 16-year-olds at a girls’ school in L.A., and then we were 30, and now we’re two 40-year-old women grinning and hugging each other on this dock in Crete? Our faces are traced with the experiences of the years – losses and loves. We have more gray hair.It’s early and we are both bleary and excited. We throw my bags into the purring 20-year-old Toyota and lurch off for Gerani via Chania, the nearest large town.

Clustered on the street corners in Chania, Eastern European men (Albanians, Bulgarians, Yugoslavs) eye the passing traffic, hoping for work as day laborers. They are a new feature of the urban landscape here, as ubiquitous as the Oaxaquenos on the street corners of L.A.

It is a hair-raising 30-minute ride from Chania to Gerani. The locals are not hesitant about passing, even on blind curves. Scotty finally noses the Toyota down a precariously narrow road, stopping in front of the blue house of the snapshot. I walk down the dirt path, an orange kitten ambushing my shoelaces. The terrace is graced by blooming succulents and shaded by a fig tree. In the distance, the sea.

The old stone house has “potential.” Wood floors and high ceilings. Two rooms above the studio, visible through the holes in the floor planks. Scotty gives me her bed in the room that looks across the valley to Gerani.

While she makes lunch I nibble a few wrinkled black olives in a ceramic dish on the round table. They are dry, but tasty. Scotty shrieks in alarm when she notices. I am eating her morning still life.

It takes a little while to get used to the amenities of the blue house. The bathroom consists of an outhouse in the olive grove. It’s important to button your pants before emerging, because the bright blue outhouse is next door to old Costas’s bean field, and he might be hoeing his rows. The “bathtub” consists of plastic buckets; indoors is just a cold tap. Taking a bath is an elaborate ritual of heating water, hanging up tablecloths in the windows with clothespins so no one can peer in. You stand in one plastic bucket and pour water from another bucket over your head.

A cock starts to crow mid-afternoon, igniting another across the valley. The milk goat chimes in. A man calls across the village for his mother to make him coffee. He sounds fairly hysterical. Scotty calls him “The Voice.”

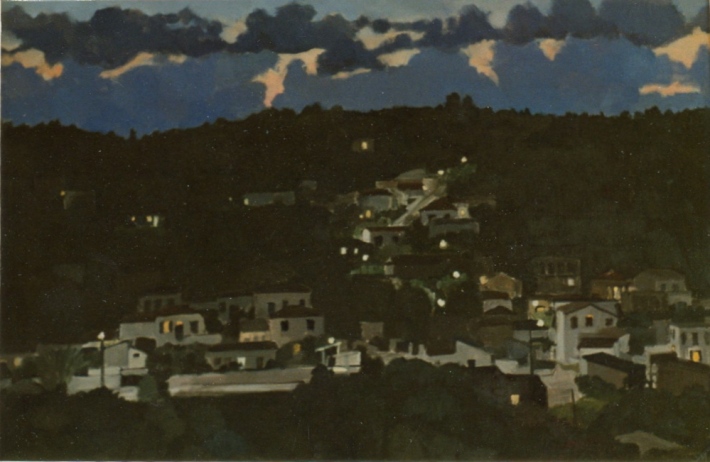

Gerani at Night

We walk down the hill behind the blue house into Gerani, carrying empty plastic jugs to fill with wine at the kafenion. We pass an old woman, Calliope, and her niece Nauseca, a friendly pudgy girl with a little beard on her chin. Scotty says she is “not quite right.” The two of them are on their way from the cemetery – the memorial day for a friend who died 40 years ago. They carry little buns and a bag of sweets (kolyva) eaten at memorials. They insist on giving me a handful: cinnamon, sugar and corn.

Today was our first expedition. Scotty wants to show me some of the villages where she’s painted over the last years. I am fascinated to see how she chooses a landscape subject. There are practical considerations, like where to park the car. There’s the foreground, the background. There are certain colors that call out to her. There is above all the light. The site must be accessible each day at the same time. “The conjunction of things has to hit you just right,” she explains. “They have to scream `that’s it!’ and sometimes it happens in the middle of the road. Or a storm blows off two branches and you realize the magic is gone.”

When she scouts for sites, Scotty stands for a long time staring: a cluster of trees; the slope of a hill; stones artfully mortared into an old wall; a series of flat red roofs. Her love of this place is intensified by her close attention to its physical details. Her eye is constantly searching for beauty in the wild, melancholy Cretan landscape. Autumn is the season for wild heather. Wild black goats clamber over the lavender clumps, luminous against the red rocks.

We eat our picnic of bread, feta and olives at a small Byzantine chapel. The door to the chapel is open. Tiny silver votive offerings of hearts, hand, feet and breasts stud icons of St. George slaying the dragon. The chapels are frequently locked now, says Scotty, because villagers fear desperate Albanians will steal the donations.

Suddenly we are rocked by an explosion. They are dynamiting the hillside down below the church. That’s how they break up rock when they want to build houses. The Greeks are fond of dynamite. Though it’s illegal, they still fish with it sometimes, setting off a charge, then netting the dead fish that float to the surface. The use of dynamite accounts for a number of accidents each year, and is one reason (the other being World War II and the civil war that followed) that you see men in the villages missing several fingers, an arm or a leg.

On days when we stay home, the day separates into two working sessions, punctuated by lunch (a good salad with olive oil from Scotty’s grove). She works on a morning painting and an afternoon painting, trying to hurry and finish the second so we can eat at the dining room table. The table is currently arranged with bowls of eggplants and red peppers, which give up more of their essence to the atmosphere each day. In short, they’re rotting.

Red Mullet

I’m tantalized by human scenarios suggested by the configuration of objects in Scotty’s paintings. It’s like seeing the stage before the players enter. Might there be a lover lying on the bed beyond the doorway, illuminated by slanting late-afternoon light? I sense the hand that will reach for an olive in the brightly patterned metal can. I conjure a relationship between two sisters suggested by the fragile blue airmail envelope lying on the table next to a vase of chrysanthemums. I smell fragrant Greek coffee brewed with those long-handled copper coffeepots hung on the wall by an unseen inhabitant. A straight-backed wooden chair looks alert and ready for the weight of a human body. These objects are invested with life and delight.

The morning rain stops and we walk through Modi, the upper village. We pass village men sitting outside the kafenion in the late-afternoon sun. I keep my eyes to myself, listening to the click of their worry beads. The landscape is ecstatic after the rain. The new grass under the vineyards is as green as the vines. The canopied and carpeted enclosure is an inviting, secret space. Handsome speckled hens peck busily in their yards. Fragrances of citrus, urine, manure.

The morning painting in which the dining room table figures is finished. Tonight we eat our lentil curry there.

We load up the old Toyota with Scotty’s easel, watercolors, pastel, oils, charcoal and canvas, my typewriter, sack of books and writing supplies. I write in the car, gazing off at a soft landscape of olives, figs, oaks, just this side of the awesome Preveli Gorge. We visited Spili this morning, after spending the night in a coast town. Spili is known for its running mountain waters, which flow out of the stone mouths of 19 lions in the town square. There is a saying, “If once you drink the water of Spili, you will always come back.”

Spili

Scotty knows everyone in the town. The old men in the kafenion, the kafenion proprietor, the cafe proprietor’s wife, the man digging ditches near the main square, the cobbler, the baker. As we walk the little alleyways up the hillside, people stop to talk, their faces light up when they recognize her. It’s been 10 years. The yiaya (grandmother) in the grocery store insists on serving us local raki, distilled from mulberry leaves. Raki burns the lips, and according to the grocery lady, Vangeliou, curls the hair on your chest.

Two days of rain knocked down several walls in the village, and two men, one quite old and bent, attempt to fix them. The old man recognizes Scotty. “Did she ever marry?” he asks. “Yes, and widowed.”

“Will you marry again? I’m available,” says the old man. Scotty manages a smile. As we walk away he yells, “I will kill myself for you!”

Plakias, on Crete’s southern coast, is our “home base” for a few days. The souvenir shops are empty, the restaurants close down day by day. A howling wind outside. A poignant desolation. A resort town without the tourists is a surreal environment. An armada of fat geese struts around, letting loose with the most unholy screeches. No newspapers in this town, a remote outpost. The eerie wind is conducive to writing but not to painting landscapes, which is what Scotty is doing somewhere. I wonder if she has been hoisted aloft by her easel.

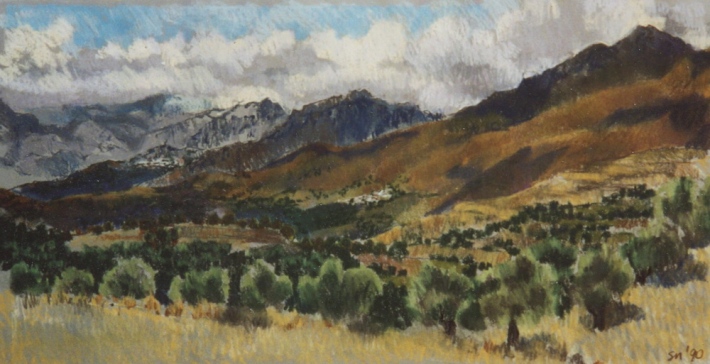

Distant Selia (near Plakias)

The only people left in this town, besides the few villagers who work here (all of whom Scotty seems to know) are all young Germans. One can imagine, at dinner, that one is in Bavaria. The package tours end in a few days. Because Crete has staked its economic future so thoroughly on tourism, when the last package tour ends, most coastal towns really shut down. There aren’t even restaurants open for the villagers, for whom a Sunday meal at a restaurant used to be a regular ritual. Instead of living rooms where families gather, one sees a solitary grandpa watching TV in a barren hotel lobby.

In the one restaurant still open, an old Cretan teaches a German tourist how to eat snails. You tap them with a fork, then suck hard. That’s how the Cretans survived the war, eating snails.

This early Sunday morning we drive from Plakias through the Preveli Gorge to its end on a steep cliff, the waves of the Mediterranean Sea slamming below. The wild gorge with its uncanny wind has been Scotty’s favorite place to paint, and her favorite spot to roam, ever since she moved to Crete. The stark landscape has always inspired her.

The locals call Preveli “Hands Clapping Gorge,” for the sound the wind makes. The old Preveli Monastery hugs the rugged slopes of this isolated landscape. Besides a few sheep, the magnificent old stone buildings are deserted. I’m surprised when a bearded man appears, in pullover and trousers. He is a priest caretaking the monastery for the weekend, and he invites us into his quarters for coffee.

The Preveli Monastery

The priest and his cohort invite us for coffee, but ply us with raki. The one with the dancing eyes surreptitiously fills my shot glass while I talk to the other toothless one. Five glasses of raki before noon! These two rascal priests admonish us to “love life, every minute of it!” They revel in my intoxication. To help absorb some raki, they serve us holy bread, which is fragrant and sweet, plus raisins and peanuts. The strong Greek coffee is untouched.

During the Battle of Crete, in WWII, the monks at Preveli sheltered British and Australian soldiers. The Germans rewarded them by burning half the monastery. In the chapel, in a glass case studded with rings, left as tokens by pilgrims, rests a piece of the “True Cross.” According to our hosts, the Germans tried to abscond with it, but their planes wouldn’t take off with the cross aboard.

There are no more monks left. The last and youngest one, age 60, had a stroke last year. Village priests now take turns taking care of the monastery; most of it is boarded up.

Not just monks are scarce on Crete. There are very few master craftsmen anymore. “Everyone wants to be a doctor, a lawyer or a pharmacist,” explains one priest sadly. Scotty suggests perhaps artists could live at the monastery, fix up studio spaces and work there. The priest solemnly thinks it over, then says, “They would enjoy the beauty here, but they are not true believers.”

Village life is not intended to be lived alone. If you can’t cut your own wood, your brother-in-law will. If you’re sick, your aunt brings you soup. But Scotty has no family here. Yesterday she cemented the crack above the front door, I dug flower beds, carried in kindling. She pruned olives, I shook down almonds. Just washing clothes by hand takes a whole morning. There are no laundromats on Crete. When I walk around Gerani I pass village women hunched over their washing – their posture a result of years of washing their father’s, husband’s, children’s undershorts.

I stand on the terrace with morning coffee and look around at all the signs of life strewn about: the brightly colored plastic buckets for washing clothes, taking baths; the hammer and the pile of almond shells from where we sat and husked the other day. The ceramic dishes with bits of sardines and macaroni clinging to them, for the cats; the box of detergent; the broken bricks for roofing; the empty easel.

These messy artifacts are not included in Scotty’s paintings. Within the universe of her canvases, there is balance, harmony and cohesion. The paintings are a respite from the rigors of her daily life, and a celebration of its pleasures.

I came here figuring the only way to really understand a still-life painter was to live in the still life. I’ve learned that what’s outside the frame is just as revealing.

At 4 a.m., I wake and walk outside, settling on the stone steps to watch the dawn of my last day on Crete. Hundreds of cocks in the valley are crowing. The sky grows lighter, a dark cloud blushing terra cotta. Dogs, goats and donkeys add to the delicate din. A shooting star flashes over the olive grove.

On this late November day, the sun is strong, no clouds and a mild wind. Fig leaves fall from their branches, the lone freesia blooms in its pot. Broom leans against easel, the kitten toys with an empty plastic water bottle. On the day I leave Gerani, Calliope milks her shaggy white goat into a red plastic bucket.

This is wonderful Scotty. Nice to see the landscapes of Crete that are precursors to what you are doing now. Beautiful life, beautiful work, beautiful artist. It is all one, isn’t it?

I do hope so and look at you!XXX

Loved reading this and knowing more of you.

Thanks Greer…if you ever come up this way please do look me up.

“Balance, harmony, and cohesion” – that’s what it’s all about, even in the midst of this perplexing, cruel world. We need artists to remind us of that. Thanks, Scotty.

Thank you Lisa…and I so hope we can get together sometime.XXX

Interesting reading your friends article about your time in Crete. I have been travelling there for forty years after living on the beach in Paleohora for a number years in the mid 1970,s. I now have a house in Spili just up to the left of the fountains, in an old lane, the old Skordalos place. Love Spili, especially the people.

I bought Watermelon years ago through Jill Yakas after you had moved to the US. I stumbled upon this blog and just wanted to say hello. It is in my living room and fondly reminds me of my time in Greece (Politea) in the 1990s.

Well, I wonder if you monitor the blog as I see the last entry was almost 5 years ago….. I too bought one of your wonderful paintings (Kitchen Window) through Jill Yakas, a friend of my brother, David Rupp. And later bought Potting Shed. Both are very special to me as a reminder of the many trips I made to Greece to be with my brother as he conducted tours each summer.

Thank you Lois. It is indeed a long time since I’ve written a blog and I’d love to get back to it.I’ve just moved to New Mexico and other considerations have been dropped for the time being

. I probably met your brother at some time. Jill and I are still in contact. i”m glad you enjoy those paintings. Best,Scotty

A great article by Louise Steinman on Scotty’s work and life on Crete. Very fond memories of time spent there with Scotty..